Common Mistakes in LabVIEW Code

Finding issues in a program and then debugging to identify errors inevitably leads to significant time consumption. To improve development efficiency, a fundamental principle is to avoid common and elementary mistakes while writing code. This approach can greatly reduce the time dedicated to debugging.

Producing code with few potential errors demands patience, meticulousness, and the accumulation of experience. Yet, some programming errors are remarkably frequent, and nearly every LabVIEW programmer has likely encountered them at the beginning stages. Highlighted below are some of the common mistakes to watch out for during programming. Being mindful of these can make your work much more efficient. These topics have been touched upon in earlier chapters of this book but are summarized here to remind readers to pay extra attention.

Numeric Overflow

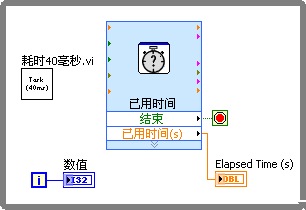

Below is an example program previously introduced in the Numeric Representation section:

This VI is tasked with a simple multiplication operation: 300×300. Intuitively, the answer is 90000. However, the outcome produced by the program is 24464. The multiplication node itself is accurate; the error arises because the data type used in the program is I16, which has a maximum representable value of 32767. Consequently, a numeric overflow error occurs during the multiplication calculation, indicating that the value has exceeded the range that the data type can represent.

To prevent such errors, it's crucial to ensure that the data within the program never surpasses the range that can be represented by the short data type in use. Short data types, as opposed to longer ones, have the benefit of conserving program storage space and enhancing operational efficiency. However, their smaller representable data range makes them more susceptible to numeric overflow errors. For individual data points (not part of arrays) where usage frequency isn't exceptionally high, the efficiency gained from using short data types is minimal and can often be disregarded. In these instances, it's advisable to opt for longer data types to avoid potential errors.

For Loop Tunnels

Shift registers in a for loop are primarily utilized when the loop requires the use of local variables; that is, the output data from one loop iteration is needed as input for the next. Data from arrays outside the loop can be accessed within the loop body through indexed tunnels. For straightforward data transfer into and out of the loop, standard tunnels are adequate.

If data is fed into a for loop structure and also needs to be output, then shift registers or indexed tunnels should be employed for this data transfer, avoiding non-indexed tunnels. This precaution is necessary because the iteration count of a for loop could be zero. Programmers often plan to use the data processed through the loop in subsequent parts of the program. However, if there are zero iterations, none of the code inside the loop, including connections between two tunnels, will execute. As a result, data will not be transferred from the input tunnel to the output tunnel, leading to the loss of the input value, rendering it unusable for later parts of the program.

The program illustrated below is designed to store a set of input data in a file:

In this example, both the file reference and error cluster are passed into and out of the For Loop via standard tunnels. When the input data constitutes an empty array, resulting in zero iterations, the for loop's code does not execute. Consequently, the file reference obtained from the loop's output tunnel is not the same as the input reference, which then prevents the program from properly closing the opened file. I have encountered and resolved programs with memory leaks caused by this very issue.

Therefore, it's imperative to use shift registers when passing handle-like data into and out of a for loop:

Likewise, error cluster data must be transferred via shift registers when moving in and out of loop structures. This approach is not only to prevent the loss of error information when the iteration count is zero but also because an error output typically signals that subsequent program segments should not execute. Proceeding with program execution after an error can be highly risky, possibly leading to program crashes or system failures. By employing shift registers, errors generated during any iteration are immediately propagated to subsequent iterations, preventing further execution within the loop structure if an error has been detected.

For more in-depth information, refer to the Loop Structures section.

Loop Iteration Count

When employing an indexed input tunnel in a for loop structure, specifying the loop's iteration count becomes unnecessary. The for loop determines its iterations based on the length of the array connected to the indexed input tunnel.

Complications arise when a loop structure has multiple indexed input tunnels or a specific iteration count, N, is also defined. This setup can inadvertently lead to programming errors. In such instances, the loop will execute a number of times equal to the smallest value among the lengths of arrays connected to the indexed input tunnels or the specified N. If the loop iterates fewer times than expected or fails to iterate at all, it's likely because one of the input arrays is shorter than anticipated.

While loops can similarly utilize indexed tunnels, their use within while loops presents a greater risk. Despite incorporating indexed tunnels, the iteration count of a while loop is governed by the stop condition, not the input array's length. When employing indexed tunnels, careful consideration is required to handle scenarios where the array size exceeds or falls short of the loop's iteration count. It might prove simpler to feed the entire array into the while loop and manage indexing inside the loop body. For situations where the loop count must align with the array size, a for loop offers a more straightforward and understandable solution. Thus, for scenarios necessitating indexed tunnels, for loops are generally more suitable.

Initializing Shift Registers

The program displayed below uses indexed tunnels in a while loop, leading to reduced clarity. Understanding the output of array out after executing the program may take a moment of thought:

Interestingly, even with a constant input value array in, the outcome for array out changes with each execution, with the array's length consistently increasing. This behavior stems from the absence of an initial value for the loop's shift register.

Uninitialized shift registers retain their data from the end of the previous execution until the VI is closed. This feature can be beneficial in certain contexts, akin to how global variables operate, by leveraging this persistence. However, when shift registers are intended to serve as local variables within loops, initializing them is essential to avoid potential errors.

Order of Elements in Clusters

The program depicted below inputs and outputs clusters named info and info out, respectively, each containing three elements: name, high, and weight. The procedure first modifies the values of these three elements within info, then transfers them to info out. Assuming the inputs are high=10, weight=21, one might easily predict the outcome to be high=10, weight=21:

However, executing this program produces unexpected results:

The root cause of this discrepancy is that the order of elements within a cluster in the data wire does not necessarily align with their visible sequence in the user interface. Element controls on the interface can be moved around, and their data sequence adjusted. By selecting "Reorder Cluster Elements" from the cluster's contextual menu, you can set the sequence of the element data:

The order depicted for the info out cluster above does not match that of the info cluster. In the example program, the aim is to modify the cluster's third element, but the interpretation of the third element differs between the input and output clusters.

To circumvent such errors and facilitate ease of use, adhere to the following guidelines when working with cluster data types:

- Always create a type definition for a cluster where it's used. Then, in all program sections that require this cluster type, employ instances of this single type definition. This method ensures that the type, order, and consistency of all cluster elements are maintained, avoiding the kind of error shown in the example. If there’s a need to alter cluster elements, updating the type definition will automatically propagate changes to all instances, negating the need for individual modifications across VIs.

- Always utilize the Bundle By Name or Unbundle By Name nodes for bundling or unbundling cluster data. These nodes visually present the labels of the elements being manipulated, preventing wiring mistakes due to variances in order.

- Opt for automatic horizontal or vertical alignment of cluster elements on the interface. This practice ensures the sequence of controls within the cluster remains consistent with the data order.

For an in-depth exploration, refer to the Cluster Data Type section.

Timing Errors

LabVIEW inherently supports multithreading, offering both convenience and potential challenges. In single-threaded programs, the execution sequence of functional modules is predetermined and fixed. In contrast, automatically multithreaded programs can have an indeterminate execution order for parallel modules, potentially diverging from the programmer's expectations and leading to errors.

Consider the program illustrated below, designed with the following sequence: initially, a file is opened; subsequently, two sub-VIs, A and B, access this file; and, ultimately, the file is closed.

A hidden problem in this VI is the uncertain execution order of the parallel sections. It's possible that during execution, the file close function is triggered before sub-VI B has a chance to run. Since sub-VI B requires access to the file, it may encounter an error if the file is already closed.

This issue can be easily circumvented. By leveraging the error cluster data wire, the execution sequence can be controlled, ensuring the file is closed only after both sub-VI A and sub-VI B have concluded their operations:

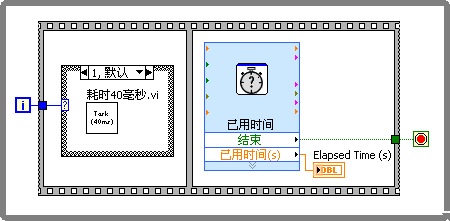

Timing errors are also common when determining the exit conditions for a While Loop. Take, for instance, the program below:

The program's objective is to execute the sub-VI "Takes 40 milliseconds.vi" repeatedly within a specific time frame. The "Elapsed Time" VI evaluates the program's runtime, prompting an immediate loop exit by outputting "True" from the "Stop" parameter once the predefined duration is surpassed. However, this program has a flaw: the "Takes 40 milliseconds.vi" and "Elapsed Time" VIs operate in parallel, with "Elapsed Time" VI completing very swiftly. In every iteration, "Elapsed Time" VI promptly returns its result, meaning the loop has to wait until "Takes 40 milliseconds.vi" concludes before it can terminate, even after the designated time has elapsed and the "Stop" parameter signals to end.

To address this, the code assessing the loop's exit criteria and the remaining code's sequence must be clearly defined within the loop body. Utilizing sequence structures to specify execution order can be an effective strategy:

Race Conditions

Race conditions are a specific type of timing error, characterized by data chaos when multiple threads access the same resource at the same time. They are most commonly associated with the misuse of global (or local) variables. To improve programming practices, it's advisable to minimize the use of global variables. When the use of global or local variables is inevitable, a standard solution to prevent race conditions involves protecting shared resources with semaphores. This means a thread needs to verify whether the resource is currently being used by another thread before accessing it. If the resource is occupied, the thread waits until it becomes available. If unoccupied, the thread locks the resource, signaling to others that it is in use, then proceeds with its operations, unlocking the resource upon completion:

This approach is akin to protecting data when using queues to pass references. Semaphore-related functions can be found under the "Programming -> Synchronization -> Semaphore" function palette. For more in-depth discussion, refer to the section on Using Semaphores to Avoid Data Race Conditions.

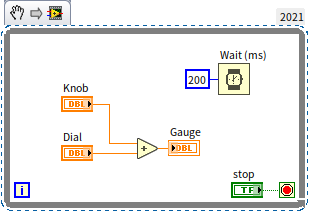

Delays in Wait Loops

The above diagram illustrates an early example from this book, featuring a loop intended to respond quickly to changes in data or state. Solely relying on loop structures for this purpose is inefficient because, in most cases, the data or state does not change, rendering many iterations unnecessary. The ideal scenario is for the program to react only upon actual changes.

However, immediately triggering an event upon any change in values or states may not always be feasible. For example, when data from an external device changes, it doesn't automatically generate an event. The only way for the application to monitor such changes is by continuously reading the data value. In these instances, the program must resort to an incessant loop, repeatedly checking if the data or state has changed. It's essential to incorporate a delay of a few dozen to several hundred milliseconds in such polling loops to prevent monopolizing the CPU for futile calculations. While this won't cause logical errors within the program, it can significantly slow down the execution of other parts of the program.