Data Acquisition, Processing, and Display

Structuring Your Program

For LabVIEW programs of a manageable size, the approach to either analyzing an existing program or designing a new one typically progresses from the overall to the specific—that is, from a high-level to a low-level analysis and design. Diving straight into the details from the get-go can prove to be less efficient.

In the design phase, developers initially segment the program into several tiers vertically. Starting from the very top, they contemplate how to split this highest layer into various sections based on the program's functions and the interrelations between these sections. Then, for each segment of this topmost layer, the next tier down is considered, further dividing it into more detailed functional modules according to their respective tasks. This layered approach continues downwards.

Depending on the program's scale and complexity, it can be divided into varying levels of hierarchy. The simplest programs might consist of just one level, accomplished with a single VI. Moderately complex programs could feature two levels, made up of a main VI and several sub VIs. For even more intricate programs, the number of levels could increase.

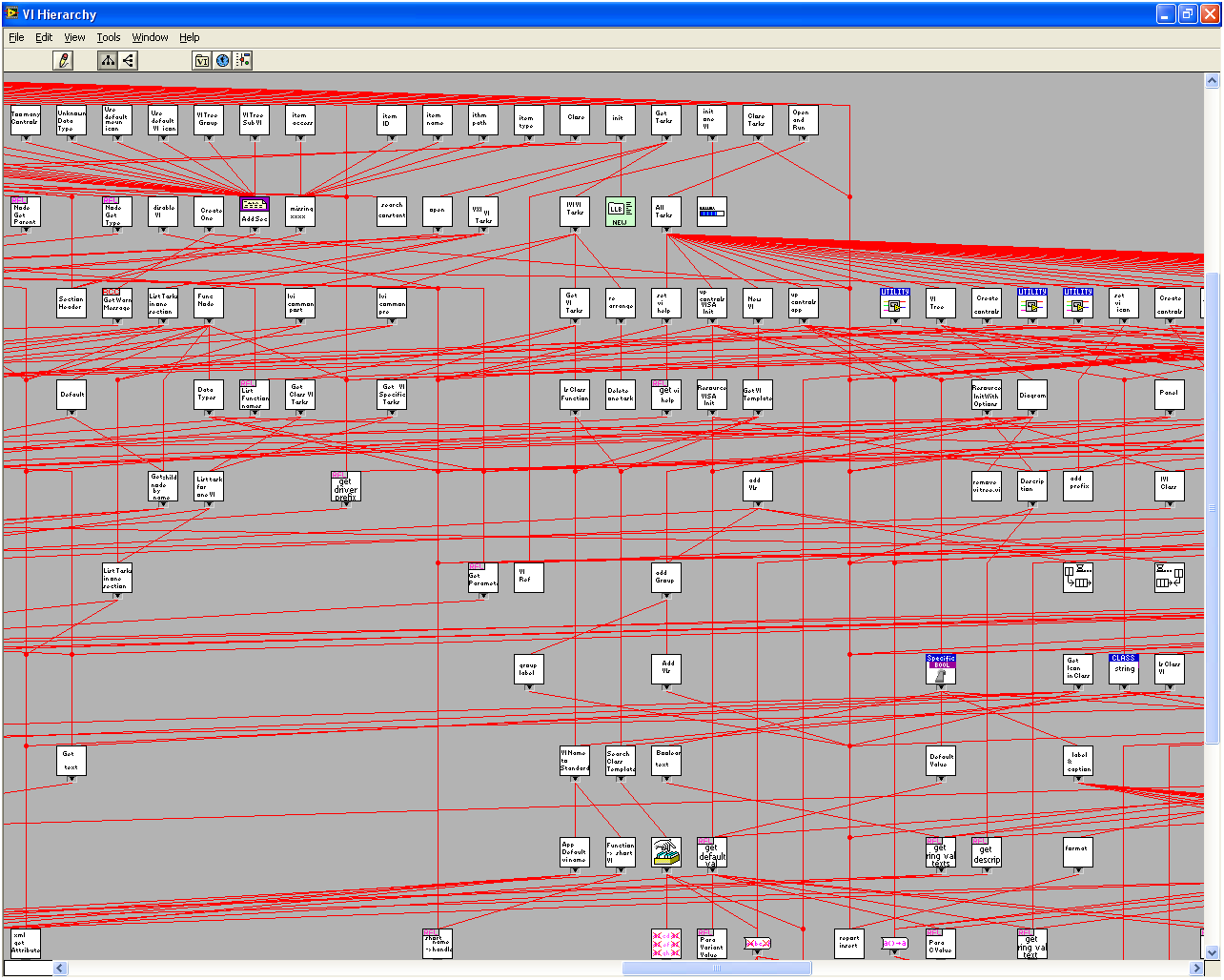

The hierarchical structure of straightforward programs is evident in the VI hierarchy (refer to Using Sub VIs). However, for larger-scale programs, the VI hierarchy diagram falls short for analysis purposes. As shown in the diagram below, only a fraction of the VI hierarchy is visible even on a full-screen display. For such extensive programs, a more abstract approach to dividing program levels is advisable.

A frequent strategy for segmenting test and measurement programs involves three tiers.

The apex tier is the main VI. Typically, a test program's main VI also serves as the interface VI, hence this topmost layer could also be termed the interface (interaction) layer. It is tasked with rendering the program's interface, facilitating user interaction, and invoking lower-level VIs.

Beneath it lies the functional layer. A test program conventionally comprises several core functionalities: data acquisition, data analysis and processing, data display, and data storage. This chapter will delve into the design and execution of these functionalities in detail.

The foundation tier is known as the driver layer. The program's diverse functions are fulfilled by calling different drivers for more specific and generalized tasks, such as drivers for data acquisition devices, file read/write operations, and graphic displays. This tier also encompasses low-level mathematical operation VIs and more. LabVIEW already equips users with a suite of standard low-level driver functionalities, thus this book will not cover drivers extensively.

The main VI employs various program structures when invoking several functional modules, adapted to the program's specific needs. Below, we introduce several structural models frequently employed in test programs.

The Standard Loop Model

The process of a straightforward test program can be broken down into data acquisition, processing, display, and storage phases. The structure of the main VI program block is illustrated below.

Typically, programs aren't run just a single time but need to continuously cycle through collecting, processing, displaying, and storing data. This cyclical program model is depicted below, essentially adding a loop to the previously mentioned structure.

In the program illustrated above, the final sub-VI is tasked with deciding whether the experiment should end or if another loop iteration is necessary. This model operates with sequential execution in a single thread. Its main advantage is straightforward program logic, making it simpler to design and comprehend.

However, this model introduces sequential dependencies between each functional module. It runs in a single thread, necessitating the completion of one module before proceeding to the next. For instance, despite data storage being a relatively slower process, the computer must wait for its completion before initiating the next loop for data acquisition, consequently slowing down the overall program execution speed.

Pipeline Model

Improving efficiency can be achieved by simultaneously running several functions. Naturally, the sequence for individual data pieces still needs to follow acquisition, processing, then display, and finally storage. Simultaneously running functions doesn't imply operating on the same data simultaneously but rather collecting new data while processing and displaying/storing the data from the previous loop iteration. This resembles a multi-stage product manufacturing assembly line.

The pipeline approach enhances program efficiency to a certain extent. In this model, the duration of one loop iteration—or the time taken to process a single data piece—depends on the longest step among acquisition, processing, display, and storage. If there's consistently one step that takes the most time, then the pipeline model is a great choice.

In reality, due to variations in data transmission speeds, the rate at which data is collected into the computer can fluctuate. Similarly, data processing speeds may vary due to other programs running on the computer. The pipeline speed is always constrained by the slowest process. Introducing a buffer to store data temporarily when data collection outpaces processing can further optimize overall efficiency. When data collection slows or processing speeds up, the buffered data can be processed.

Producer-Consumer Model

Building on the buffering concept for collected data, the resulting program model is depicted below.

In this instance, a queue serves as the buffer, although alternatives like arrays could also be used for data buffering. Newly collected data is directly placed into the queue, a procedure that is incredibly time-efficient. That is, data collection speeds directly influence how quickly data can be stored in the buffer. Another section of the program consistently extracts data from the queue for processing. Additionally, the data display and storage components of this model could be run in another separate loop, if necessary.

This approach is known as the "producer-consumer model". The upper loop in the model acts as the producer (collecting data), while the lower loop acts as the consumer (processing data). Templates for this model can be found in LabVIEW's New Dialog.

At first glance, programs adopting the producer-consumer model may seem complex. However, once the roles of the two primary loops in these programs are understood, analysis becomes simpler. Actual applications of this model tend to be more intricate and, compared to the pipeline model, more challenging to grasp and maintain.