Interface

The Essential Distinction Between Interfaces and Classes

Before we delve into the specifics of interfaces in LabVIEW, it's crucial to understand the key distinctions between classes and interfaces, as discussed in the section on the pros and cons of classes:

- Class inheritance aims to utilize the functionalities already available in a parent class; implementing an interface ensures that a class can offer certain functionalities. For instance, if a class for the instrument model LV12345 inherits from the Oscilloscope Class, it suggests that LV12345 is a type of oscilloscope that relies on the functionalities already implemented in the oscilloscope class. Conversely, if the LV12345 class implements the Oscilloscope Interface, it doesn't categorize LV12345 under any instrument type but signifies that it will provide the functionalities typical of an oscilloscope.

- A class can only inherit from one parent class; however, a class can implement multiple interfaces. If the LV12345 class inherits from the Oscilloscope class, it cannot inherit from the Spectrum Analyzer class. The LV12345 class can implement both Oscilloscope and Spectrum Analyzer interfaces, indicating it can serve both as an oscilloscope and a spectrum analyzer.

This distinction highlights that interfaces, rather than classes, should be used as the type for input/output controls when a functional module is required in an application (e.g., using oscilloscope functionality to record the waveform of an input signal). Using a class for input/output types limits the application to using only oscilloscopes, excluding those instruments that have oscilloscope functionalities but do not fit into the oscilloscope category. Clearly, the application needs not a specific oscilloscope but any instrument offering oscilloscope functionalities.

In several programming languages, interfaces are not just for defining a class's externally accessible properties and methods. They also serve to ensure abstraction and minimize code duplication.

Abstraction means that interfaces cannot be instantiated; they lack objects. Thus, classes and interfaces distinctly separate functionalities. For example, in Java, interfaces are commonly used as function parameter types, whereas the actual parameters are objects of specific classes. Continuing with the previous example, an application that requires oscilloscope functionality should utilize an oscilloscope interface to operate any instrument that fulfills the required functionality, regardless of the instrument's model. Every instrument always represents an instance of a specific type of instrument class, and there shouldn't be an instrument in the program that doesn't belong to a specific type. This method prevents programmers from inadvertently writing incorrect code.

To reduce code duplication, some languages allow default implementations for methods within interfaces. These default implementations can be directly utilized by classes that implement the interface, avoiding the need to add similar code repeatedly in every class that implements the same interface.

In LabVIEW, interfaces resemble classes but with two main distinctions: 1. Interfaces contain no data, and 2. Interfaces can be inherited by multiple classes. LabVIEW interfaces primarily function to define the methods a class can expose externally. However, their ability to ensure defined abstraction and reduce code duplication is somewhat limited. Therefore, when employing interfaces in programs, it may be necessary to undertake additional design measures to reinforce these aspects of interfaces.

Creating Interfaces

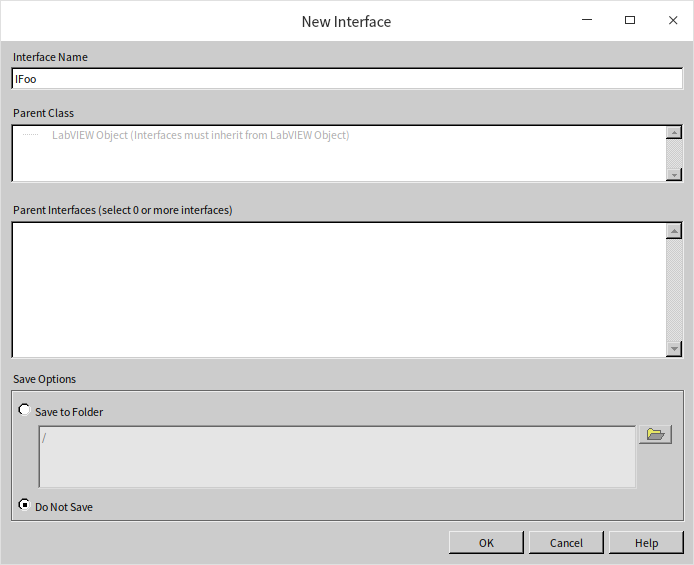

Creating a new interface in LabVIEW mirrors the process of creating a new class: right-click in the Project Explorer and select "New -> Interface" to initiate a new interface. The "LabVIEW Object" acts as the root ancestor for all interfaces. Unlike classes, interfaces cannot inherit from any classes but can inherit from other interfaces. For the initial interface created within a project, there won't be any existing interfaces from which to inherit:

The file extension for an interface is lvclass, identical to that used for class files. It’s common in projects to have a class and its corresponding interface share the same name, for instance, a Table class and a Table interface, making distinction based solely on file extension impractical. In English contexts, it's customary to prefix interface names with an "I", denoting Interface, such as ITable for a table interface. LabVIEW imposes no stringent naming conventions for classes and interfaces as long as the naming aligns with the organizational or company standards.

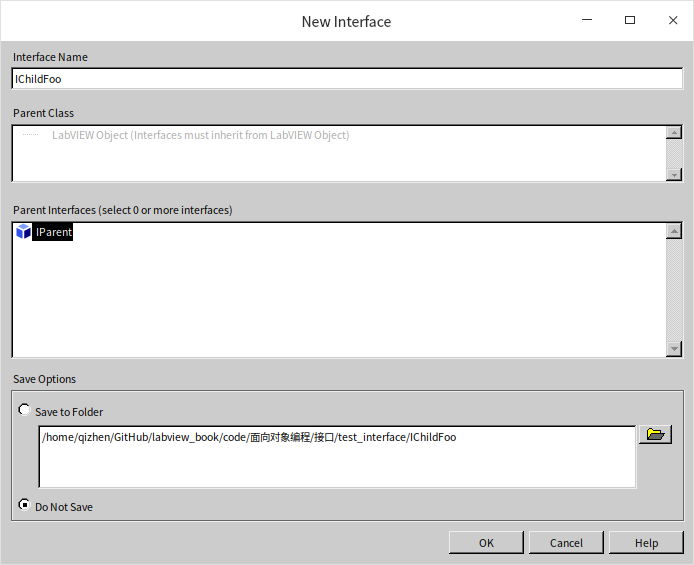

Interfaces can maintain inheritance relationships, akin to classes. For example, we might first create an interface named IParent, then create another interface named IChildFoo, setting it to inherit from IParent:

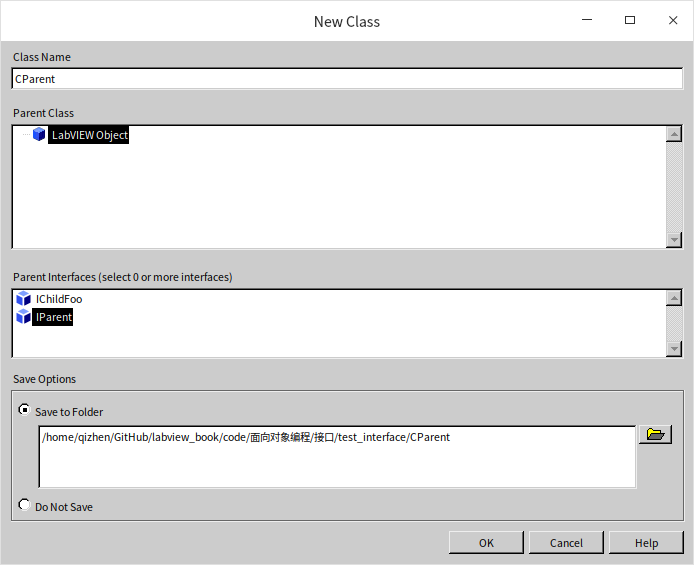

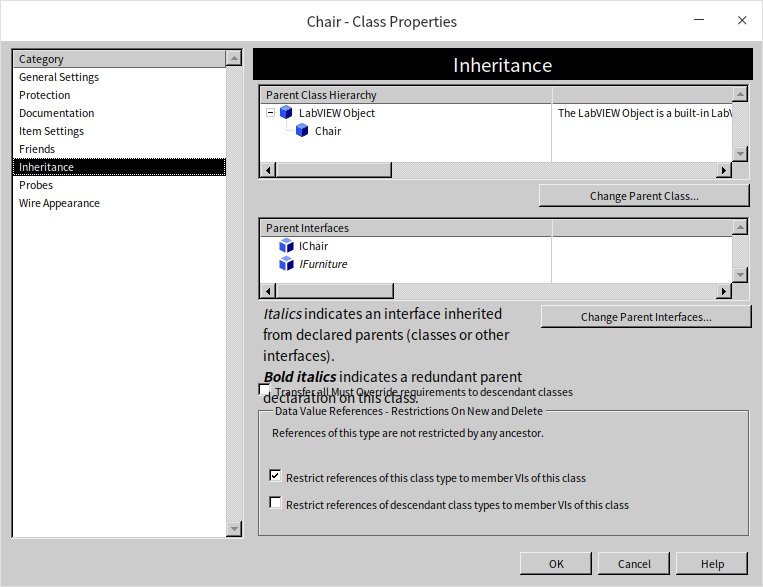

We then proceed to create some classes and select their applicable interfaces. While only one parent class can be selected, multiple interfaces can be inherited (or none at all):

Properties

LabVIEW interfaces cannot contain any data definitions. Interfaces are designed to specify which data and methods a class exposes externally. However, as all data within LabVIEW classes are private and thus inaccessible externally, interfaces naturally cannot include data definitions.

Methods in Interfaces

Creating methods within an interface follows a similar process to creating methods within a class. When adding new content under an interface, options such as VI, Virtual Folder, Dynamic Dispatch Template VI, Static Dispatch Template VI, Overriding VI, and Type Definitions appear. Unlike classes, interfaces lack "Property Definition Folder" and "VI for Data Member Access" due to the absence of data fields. The options for VI, Virtual Folder, Overriding VI, and Type Definitions are very much akin to their class counterparts. However, Dynamic and Static Dispatch Template VIs require a deeper look.

VI Based on a Static Dispatch Template

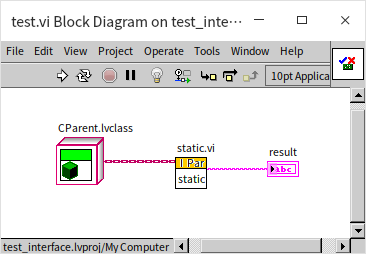

Creating a VI based on a static dispatch template within an interface suggests that this method cannot be overridden by any derived interfaces or classes. Yet, it can be inherited by them. This means instances of derived classes can directly invoke the VI implemented in the interface:

Effectively, this approach allows for adding default method implementations in the interface, accessible directly by descendant classes. However, due to interfaces lacking data definitions, a static dispatch template VI cannot manipulate any data within an object, limiting it to general operations that might not necessarily fit within an interface. In essence, while LabVIEW restricts ideally shared code from being placed in interfaces, it does permit shared code that might not suitably belong there. This significantly limits how interface method inheritance can aid in code efficiency enhancement.

A class implementing different interfaces can have VIs with the same name based on a static dispatch template in each interface. As these methods are not subject to being overridden and their invocation path is explicit, they do not suffer from the confusion that can arise with multiple inheritances in classes.

Dynamic Dispatch Template VIs in Interfaces

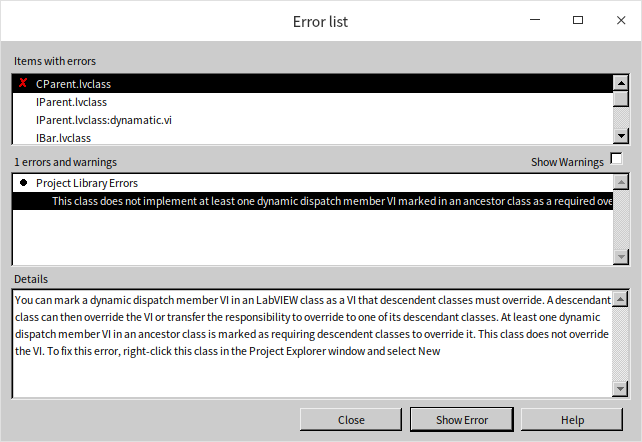

Creating a Dynamic Dispatch Template VI within an interface implies that any class implementing this interface must override this VI. If not overridden, LabVIEW signals an error as illustrated below.

In most cases, altering this setting isn't necessary. Consequently, a VI in the interface needs to be overridden, indicating its code shouldn't execute; instead, the class that overrides it will. Thus, dynamic VIs in interfaces are mainly to define the method's name and the types of its input/output parameters. A class that implements various interfaces can have Dynamic Dispatch Template VIs with identical names and parameters. Since the interface's VI needs to be overridden in the class, it's clear that the class's overridden method is executed upon calling. This clarity prevents the confusion that class multiple inheritances could cause.

By default, an interface's Dynamic Dispatch Template VI can't be called by descendant classes. As previously mentioned, interface methods are quite limited in their capabilities; even if a default implementation were provided, it wouldn't significantly enhance programming. However, if one insists on using the default implementation of a Dynamic Dispatch Template VI in an interface, it's feasible by deselecting the "Must be overridden by descendant classes" option. This allows descendant classes to inherit the interface's method default implementation. LabVIEW restricts the default implementation of interface methods for multiple inheritances; if a class implements different interfaces with the same dynamic VI, the descendant class must override this method. This ensures any program using this class's object will clearly understand the method being called is the one overridden in the class, not implemented in any interfaces, thereby avoiding confusion in multiple inheritance scenarios.

LabVIEW typically errors out in complex situations or where there could be confusion, to mitigate potential risks. For instance:

- If a class implements different interfaces with dynamically named Template VIs that differ in input/output types or connection patterns, the class cannot be correctly implemented and will always result in an error. An overriding VI can only meet the demands of one interface, leaving the other unmet.

- If a class implements different interfaces with a method named the same, but defined as static in some interfaces and dynamic in others, the class cannot be correctly implemented. Failing to override this VI would cause an error for not overriding a dynamic VI in the interface; whereas overriding it would trigger an error for overriding a static VI in the interface.

LabVIEW's functional limitations may prevent the implementation of some common functionalities. For example, suppose there's an instrument model LV12345 that functions both as an oscilloscope and a spectrum analyzer. If the oscilloscope and spectrum analyzer interfaces each define an "initialize" method with different parameters, the LV12345 class cannot implement both interfaces. Even if both interfaces define an "initialize" method with identical names and parameter types, if the required actions differ, the LV12345 class still cannot be correctly implemented. The class can only implement one initialize method and cannot determine if it's being called by the oscilloscope or spectrum analyzer interface, thus unable to decide how to set the switch.

To prevent the aforementioned issues, it's advised that interface design should aim to avoid using methods with identical names in related interfaces. Extending method names, such as "initialize oscilloscope" for the oscilloscope interface and "initialize spectrum analyzer" for the spectrum analyzer interface, could offer a solution.

Access Permissions

In an interface, VIs have similar access permissions to those in a class. However, considering the purpose of an interface is to outline functionalities a module makes available externally, it's preferable to exclude functionalities not meant for external use from the interface. Essentially, methods defined in an interface should generally be public.

Retrofitting Existing Classes

Interfaces in LabVIEW are relatively new, but they can be applied to pre-existing classes. To do this, first create or add the necessary interfaces within the same project. Then, by accessing the class's properties dialog, you can adjust its parent class and any interfaces it implements:

After integrating an interface into a class, it may be necessary to add or modify some of the class's methods to comply with the interface's requirements.

Application Example

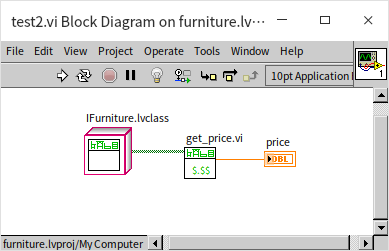

Let's revisit the furniture store program discussed in the LabVIEW Classes section. It had notable deficiencies, such as allowing the creation of furniture that is neither a chair nor a table and not enabling programs that process chair objects to also accept combo chair-table objects. These issues can be addressed by introducing interfaces.

We suggest the following adjustments to the program design through the use of interfaces:

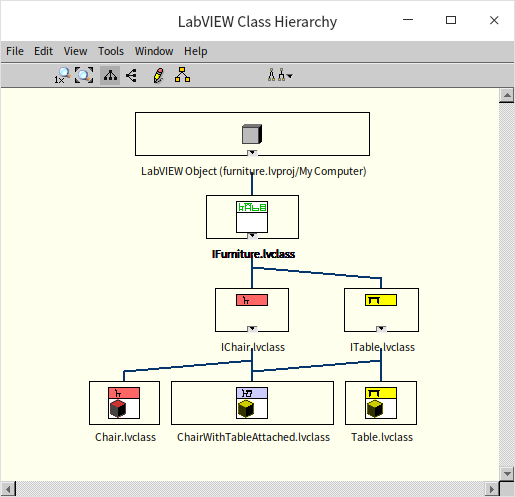

- Initially, we require three interfaces: Furniture Interface, Table Interface, and Chair Interface. Both the Table and Chair Interfaces inherit from the Furniture Interface.

- Interfaces do not contain data but can include controls for user-defined data types, such as controls defining different tablecloth types.

- The Furniture Interface specifies two methods: Return Price and Assemble. These are universal methods shared by all furniture objects.

- The Table Interface outlines three methods: Return Price, Assemble, and Lay Tablecloth. The Return Price and Assemble methods are inherited from the Furniture Interface.

- The Chair Interface also defines three methods: Return Price, Assemble, and Place Cushion, with Return Price and Assemble methods being inherited from the Furniture Interface.

Since instances of tables and chairs are required in the program, the Table Class and Chair Class are still necessary:

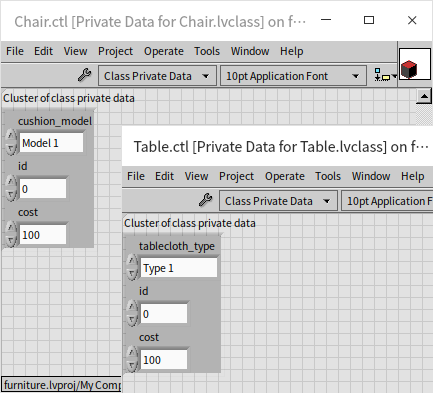

- Table Class: Implements all methods defined by the Table Interface, including an initialization method (to set product ID, cost price, and tablecloth type).

- Chair Class: Implements all methods defined by the Chair Interface, including an initialization method (to set product ID, cost price, and cushion type).

The initialization method, which lacks a class (or interface) type input parameter, can't be constructed as a Dynamic Dispatch Template VI and therefore can't be defined within an interface. Additionally, we introduce a ChairWithTableAttached class to showcase a class implementing multiple interfaces, complete with tests for it.

- ChairWithTableAttached Class: Implements all methods defined by both the Table and Chair Interfaces, including an initialization method (to set product ID, cost price, tablecloth type, and cushion type).

Creation

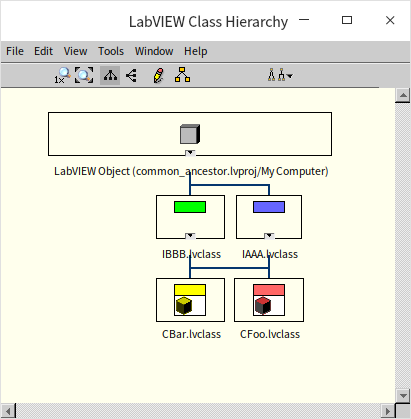

The process for creating interfaces and classes has been covered previously and will not be repeated here. By accessing LabVIEW's "View -> LabVIEW Class Hierarchy", you can see the inheritance relationships between the new program's interfaces and classes as illustrated below:

Attributes

Compared to the previous example that exclusively utilized classes, in this demonstration, we opted for a Furniture Interface in place of a Furniture Class. While we've discussed the advantages of using interfaces before, here we encounter a drawback: it's not possible to place commonly shared data and method code within the interface. As a result, the implementation of shared data and methods had to be dispersed across the specific classes. For instance, in the new example, the Table Class, Chair Class, and the ChairWithTableAttached Class each independently include identification numbers, cost prices, and other data that could have ideally been shared.

The shared data access functionalities previously implemented in the Furniture Class also needed to be duplicated in each class.

Methods

Since the methods defined within interfaces are expected to be overridden in classes by default, LabVIEW will flag an error if a class does not override a method defined in an interface. New classes may lack numerous methods; at this juncture, by selecting "New -> VI for Override", you can choose all the missing VIs simultaneously and generate them.

The methods are implemented in a manner similar to what has been previously illustrated in the examples, hence will not be detailed further here.

Application Testing

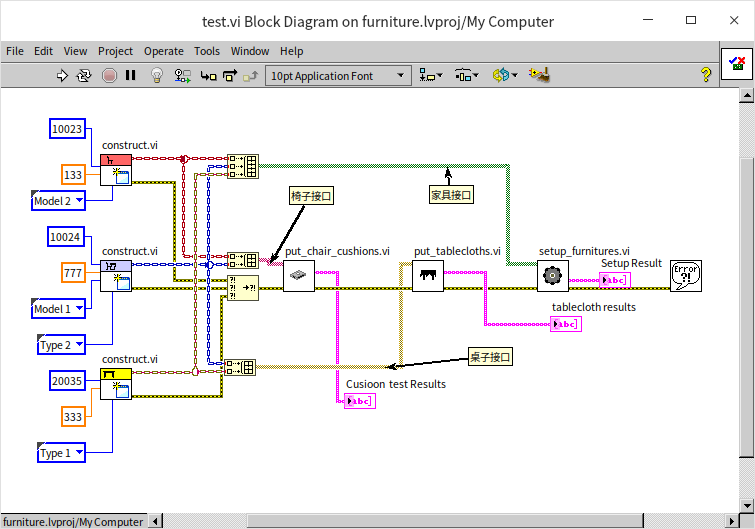

The test program closely resembles the earlier example that used classes exclusively. However, this iteration of the test program creates three objects from distinct classes:

Binding a chair object and a combo chair-table object into an array causes LabVIEW to classify the array as an array of the chair interface type. This adjustment allows both objects to be processed by programs designed to accept the chair interface. Similarly, binding a table object and a combo chair-table object into an array prompts LabVIEW to classify the array as an array of the table interface type. Binding three different objects into an array leads LabVIEW to classify the array as a furniture interface type.

If two objects lack any common ancestor interface, binding them into an array will result in LabVIEW classifying the array as a "LabVIEW Object", thereby enabling the processing of any type of object.

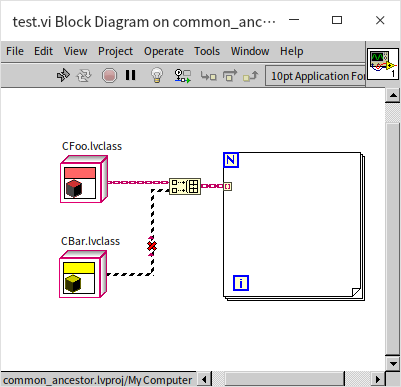

However, there's a scenario where LabVIEW triggers an error: if several distinct objects share multiple common ancestor interfaces and these objects are bound into an array, LabVIEW will face uncertainty regarding the intended interface for use, causing an error. For instance, as depicted below:

The classes CBar and CFoo each implement the IAAA and IBBB interfaces. In such cases, binding a CBar object with a CFoo object into an array will result in an error, signaling a type conflict:

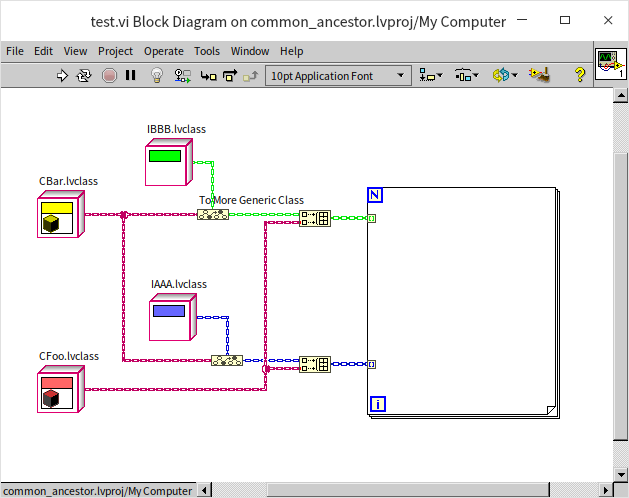

Encountering such situations necessitates the programmer manually specifying the intended interface type:

Why LabVIEW Interfaces Aren't Abstract

In the furniture store demo program, we ideally shouldn't allow the existence of a furniture object that isn't classified as either a chair, a table, or a combo chair-table. Since the program only defines these three categories, any object not fitting into them likely indicates a programming oversight. In this demonstration, we replaced the furniture class with a furniture interface. Unfortunately, this change alone doesn't prevent the direct instantiation of the furniture interface. LabVIEW interfaces aren't abstract; you can directly instantiate an interface on the block diagram and then call the methods defined within:

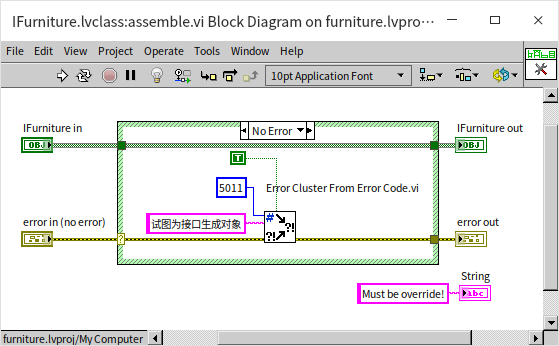

Effective interface design should ideally prevent misuse by programmers, necessitating protective measures for such scenarios. The methods defined in an interface, based on the dynamic dispatch template, are expected to be overridden by descendant classes. Thus, in normal circumstances, the code within an interface's VI should never execute. If it does, it suggests the method was called by an object directly generated from the interface. Reporting an error in such cases can alert programmers to correct the mistake. Therefore, even though interface methods likely won't be executed, it's recommended not to leave them empty but rather to return an error message to prevent potential issues. Below is a block diagram for a method VI within an interface:

The lack of abstract classes in LabVIEW fundamentally boils down to the platform's design, where data types cannot be defined separately from data. LabVIEW requires actual data to represent data types. Unlike many programming languages that have keywords for data types, like "int" for integer types, LabVIEW lacks similar keywords (or constants, controls, nodes, etc.). LabVIEW necessitates the use of specific values, like 0 or 23, to denote integer data types. Recall the example of forcibly converting a double to an integer from the "Numeric Data" section:

To indicate the target data type as I64, we use a value of 0, even though we don't actually need a value of 0 for this purpose. In the "Manually Specifying the Interface Type" example, to convert a CBar class object to the IAAA interface type, an instance of IAAA type is used to represent the IAAA type. This design in LabVIEW, where data types and data are inseparable, might not be particularly logical, but it appears to be too ingrained to change.

Enhancing Code Reusability

The furniture store example also highlights a common issue: the presence of redundant code. For instance, similarly named VIs across different classes tend to have very similar implementations. Unfortunately, we cannot consolidate their shared logic within the interface due to the absence of necessary data fields. A straightforward approach to mitigate this problem is to create sub-VIs for these common operations, which can then be utilized across classes to increase code reusability.

Summary

In wrapping up this section, let's distill the key recommendations for employing LabVIEW interfaces, drawn from the experiments and discussions above:

- Prefer interfaces over classes for defining functionalities that a module exposes for external invocation.

- Strive for singularity in interface functionality, avoiding the amalgamation of disparate functionalities within a single interface.

- Limit interfaces to defining public methods that a module (the class implementing the interface) offers for external interaction, steering clear of specifying internal methods or their implementations.

- Ensure interfaces only encompass VIs based on dynamic dispatch templates, mandating that these VIs be overridden in descendant classes.

- Objects instantiated directly from interfaces should solely serve for type conversion purposes to derive the interface data type, and not for invoking methods within the interface. If a VI from the interface is directly invoked, it should promptly issue an error message.

- Aim for detailed method naming to sidestep potential name clashes.

- When an interface is implemented by multiple classes, consider creating supplementary sub-VIs to foster code reusability.